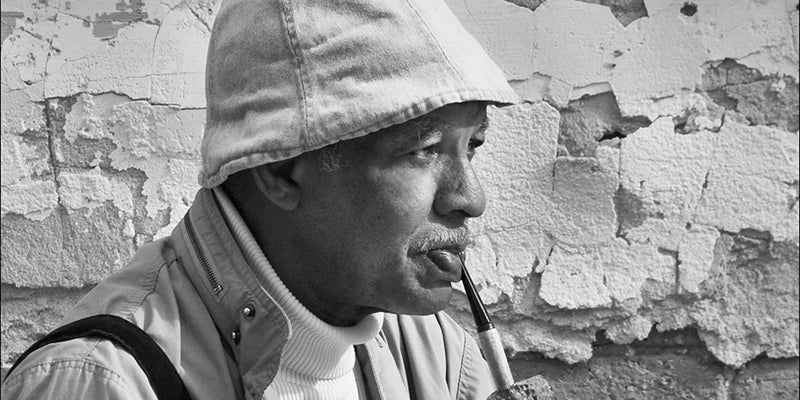

Family remembers Anderson’s life, career as photographer, artist

Published 12:48 pm Monday, September 2, 2019

Family and friends of William James Anderson Jr., took time to remember Anderson’s life and career that brought him right into the middle of the Civil Rights movement with his art and photography.

Anderson was born Aug. 30, 1932 and died July 16 of this year.

When Anderson was 33, he was in Selma with his Nikon camera and remembered well the Sunday, March 7, 1965, that would come to be known as “Bloody Sunday”.

During the march, James Reeb, a social worker and Unitarian Universalist minister, was severely beaten and later died from his injuries. Reeb was taken to the Burwell Infirmary before being transferred to another medical facility. William’s middle brother, ACE, drove the Burwell ambulance to the Infirmary, according to Anderson’s daughter, Lila Lucas.

Williams photographs of the “Bloody Sunday” march, as well as most of his photographs are now in prestigious collections worldwide.

“Much of his life’s work comprised of images of African American culture and society in the Deep South, particularly in the Alabama, Georgia, South Carolina, and Mississippi with a focus on impoverished African Americans and other rural families, religious gatherings, poverty and homelessness in the cities, life on the Sea Islands, political rallies and riots, and the Civil Rights marches and commemorations,” wrote Lucas. “Although he was primarily known as a black photographer and artist, he preferred to be known as a ‘Photographer and Artist’. He felt the color of one’s skin should not have bearing with what one wanted to do with their life. That said, his memories and experiences did set the groundwork for his compassion to be the voice of those never seen nor heard. Voices that called out the social injustices and inequity. His work was driven by his humanitarian concerns for people and their life struggles. Through his work, he was able to capture the emotional, spiritual, and state of human existence that might not have been made conscious to a world of social injustices and inequity, economic deprivation of lives of impoverished African Americans and rural families in the southeast.

His photos from Selma as well as other locations, paintings, prints and sculptures, are now in esteemed and coveted collections.”

Anderson also was interested in religion.

He was raised in the Selma Presbyterian Church. He followed the work of Dr. Albert Schweitzer who was forming a hospital in West Africa and raised funds for the hospital by giving lectures, organ concerts and writing books.

Anderson’s art piece “Madonna and Child” was commissioned by Schweitzer for his hospital in the Gabon province of French Equatorial Africa.

“I believe there is beauty in all life. From dilapidated houses and rundown farms, to old grayed gentlemen, there is simplicity that I want to capture. In my trips to various places I don’t look for the affluent and prosperous. Instead, I look for a fast-declining group of people who have really lived and enjoyed the living,” Anderson said in a 2003 interview in a Morehouse College publication. “I look for people whose faces tell a story. They know what life is about and I want to show this to the world.”

Anderson is the recipient of many awards including the Shuston-Gimbel Award for study in 1961-1962, the Henry Bellamann Foundation Grant for sculpture in 1966 at Instituto Allende, San Miguel, Mexico. He has major works in museums and major galleries around world, including the Wadsworth Antheneum in Hartford, Connecticut, the High Museum in Atlanta, Georgia, and the Corcoran Gallery in Washington, DC., king-Tisdell cottage, Savannah, Georgia, State of Georgia Department of Archives and History, Atlanta, Georgia, DuSable Museum, Chicago, Illinois, Museum of Modern Art, Syracuse, New York, and Atlanta Life, Atlanta Georgia.

His work is in notable collections including Bodlieian Library, (Oxford, England); J. Paul Getty Museum (Los Angeles, California); National Gallery of Art (Washington, D.C.), the Paul Jones Collection (University of Delaware); and the Hampton University Collection. Anderson is also published in several publication listings, Academia Internationale Contemporary Artists, Parma, Italy, Artist’s Diary, Cambridge, England, Who’s Who Among African Americans, Who’s Who in American Art, Art History Book on Collection of Paul Jones and the University of Delaware, to name a few. He is also referenced in many textbooks, “Sculpture: Technique-Form-Content” by Davis Publications Arthur Williams, “Sculpture: Technique-Form-Content Edition II” by Davis Publications, Arthur Williams, “African American Art and Artists-Revised Edition” by University of California Press, Berkeley, Dr. Samella Lewis author and “Creating and Defining The African- American Community” by Morehouse College Association for the Stud of African American Life and History, published by Tapestry Press, Ltd.

“One of my father’s quotes, ‘I feel a close kinship with the people I portray in my art. I believe that my work will have a profound meaning to the common people as well as the affluent.’ Art and the people he captured in his work were dear to his heart and his artistic philosophy and he always presented the beauty and human dignity of people through his camera lens and other art mediums,” Lucas said. “My father was very proud of his work and wore his accomplishments on his shoulders. He had a humble spirit and was always well received with anyone that he met. My father always told me and many others, he did not care about sitting around a table, eating or talking. He just wanted people to see his art.”