EPC’s Black Belt series shows a region struggling to survive

Published 4:10 pm Friday, October 30, 2020

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Over the last several weeks, the University of Alabama’s (UA) Education Policy Center (EPC) has rolled out a series of policy briefs examining the various challenges facing the Black Belt, that stretch of land across the state’s midsection whose very definition is the subject of debate and research.

Led by EPC Director Dr. Stephen Katsinas and a team of student researchers, the EPC study looked at a variety of issues plaguing the Black Belt, including declining population, falling K-12 school enrollment, unemployment, diminished labor force participation, access to pre-kindergarten programs, the region’s cloudy definition, healthcare challenges, internet access disparities and stunted economic prospects.

For Katsinas, the exhaustive project was a labor of love.

“What motivated us is that we care,” Katsinas said, noting that no such study had previously been conducted regarding a region of the state that leaders have long known to be struggling. “We knew this was there as an issue and it’s been there a long time.”

While some of the briefs recommended possible policy ideas to address the region’s social ills, Katsinas said the main point of the study was to define, in specific terms, what challenges the region is facing in order to encourage long-term solutions.

“I think what we were trying to do was simply raise some issues,” Katsinas said. “We had a sense of what the data would show and it did – declining population means declining K-12 enrollment; we expected to find higher unemployment and lower labor force participation…we expected to find healthcare issues. We did not anticipate the difference to be so start and we hope that this can lead to some longer-term efforts.”

One of those efforts, Katsinas said, includes the recent push to get widespread participation in the 2020 U.S. Census, the results of which determine how federal funding is spent for a variety of state programs and how many representatives each state gets in Congress, though more will have to be done to stave off future crises.

“Kenneth Boswell and his team at [the Alabama Department of Economic and Community Affairs] ADECA deserve a tremendous amount of credit for their successful efforts to get everybody counted in Alabama,” Katsinas said. “Because of those efforts, we may not lose a congressional seat in 2022. But if we don’t address the Black Belt issues as a state, Alabama could lose two seats off the 2030 census. So, we need a strategy…[but it] must be very different for the Black Belt than it is for urban Alabama given the lack of economies of skill that each and every institution has in the region, from hospitals to government services to education.”

The nine policy briefs found a world of disparities in the Black Belt, beginning with tumbling population numbers – whereas the 43 counties considered outside of Alabama’s Black Belt saw population increases parallel to statewide increases between 1990 and 2018, Black Belt levels remained stagnant or declined.

Of the 24 counties considered part of the region, 16 saw a loss of population in both decades between 1990 and 2018 – Selma, which saw its population fall by 17 percent from over 21,000 in 2010 to 17,200 in 2019, saw the state’s highest loss of population.

“Sadly, this trend may continue in for the foreseeable future, as persistent issues such as hospital closures and lack of broadband access drive people away,” the EPC brief stated. “The sudden requirement for remote learning due to the pandemic exposed crevasses in available broadband services that echo the gulf in electricity access in the 1930s between the rural have-nots and an urban America that had been wired for nearly two generations.”

A similar trend was found in school enrollment numbers – while the state saw a one-percent decrease in school enrollment between the 1995-1996 school year and the 2019-2020 school year, school enrollment in the Black Belt tumbled by 13 percent.

“This means that school enrollment across the rest of Alabama increase by 22,217,” the EPC education brief stated. “The 32,938 decline in the 24 Black Belt counties over the past 25 years represents a community roughly a third larger than the size of Selma.”

Where unemployment is concerned, the EPC’s research showed that the region’s rate closely parallels statewide trends over the last two decades, but is often as much as four points higher – the 18 counties with the highest unemployment rates are all located in the Black Belt with some having rates more than twice as high as the statewide average.

Additionally, while the state saw labor force participation rates moving in the right direction over the last several years, the 24 counties considered part of the Black Belt had a collective rate more than 20 points below the statewide average.

“This reality has important consequences on every aspect of life in these rural counties and the people who live in them,” the EPC brief stated. “Our challenge is to make work pay, so that the Black Belt’s best export is not their people.”

By contrast, access to pre-kindergarten and early learning programs was one of the bright spots in the report, though some areas in the region are well below the statewide average of 37-percent enrollment.

When it came to defining the region, the EPC found that “[d]espite a widely-understood if not generally-accepted knowledge base about the region, no consistent Black Belt definition is used by state or federal agencies, or by researchers.”

For Katsinas, this issue is the first which must be addressed before progress can be made.

“If you don’t define it, you can’t measure it,” Katsinas said. “So, that’s the first step. If you don’t do that, nothing else will matter.”

Where healthcare challenges are concerned, the EPC study found that the17 of the 24 Black Belt counties are below the statewide average of 3.9 hospital beds per 1,000 citizens by county, with four Black Belt counties – Lamar, Lowndes, Perry and Pickens county – lacking a hospital.

The report noted that rural hospital closures, which numbered seven in the state as of February, continue to be a problem for the region and could pose a bigger problem as 17 more remain vulnerable.

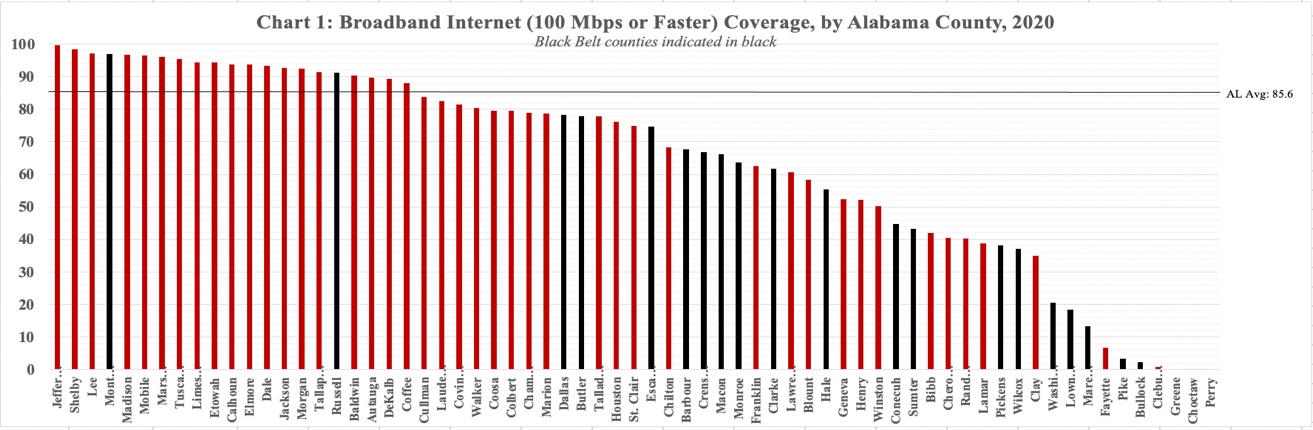

Access to high-speed, affordable broadband internet, which has become a necessity as wide swaths of society have migrated online, continues to be a problem for the Black Belt as well, with all but two Black Belt counties below the statewide average of 86 percent of citizens with access to 100 megabits per second (mbps) broadband – half are below 50 percent, while Green County has 0.2 percent coverage and Choctaw and Perry counties have zero percent coverage.

The results, though slightly better, were similar when lower internet speeds were considered.

In its final brief, published earlier this week, the EPC found that the region lags the state in business and Gross Domestic Product (GDP) growth – only four Black Belt counties were above the statewide average of 15 businesses per 1,000 residents and only three were above the state’s average for GDP.

Further, all Black Belt counties aside from Montgomery County were below the statewide personal income average of $43,229, with 10 of the 14 counties with the lowest personal income per capita in the state in the Black Belt.

Katsinas noted that each issue feeds into the next – none exist in a vacuum, isolated from the others – and that it will take a comprehensive and strategic plan to lift the region out of despair.

And while the EPC’s work researching the region is complete, Katsinas is optimistic that the research lays the groundwork for the policy work, which will be carried forth by lawmakers and other community stakeholders, still on the horizon.